Every now and then a new post about how to work with a stack, regardless of library is published. Having done a lot of work in React, there seems to be few posts that cover a well defined architecture.

Front End projects are unique in a way, because unlike many back-end systems and legacy front-end libraries and frameworks, we can reuse more modules of code. In an abstract level, this is essentially what happens in module bundlers as well. We recognize those modules the same, and glue them together to spit out chunks of code that are optimized for our application, which again makes the user experience better in effect of faster parse and load time on webpages.

Architectural wise, we can relate to this with a different perspective. When we build a front-end project with reusability and user experience in mind, we can come up with a clean structure which is easy to navigate around. This is reflected in terms of developer experience.

There is all kinds of combinations to a well defined project structure and how you choose to structure a Front End application built with React is dependent on which condition your project is in. Before expanding on that thought, let us define a good baseline for a traditional React application.

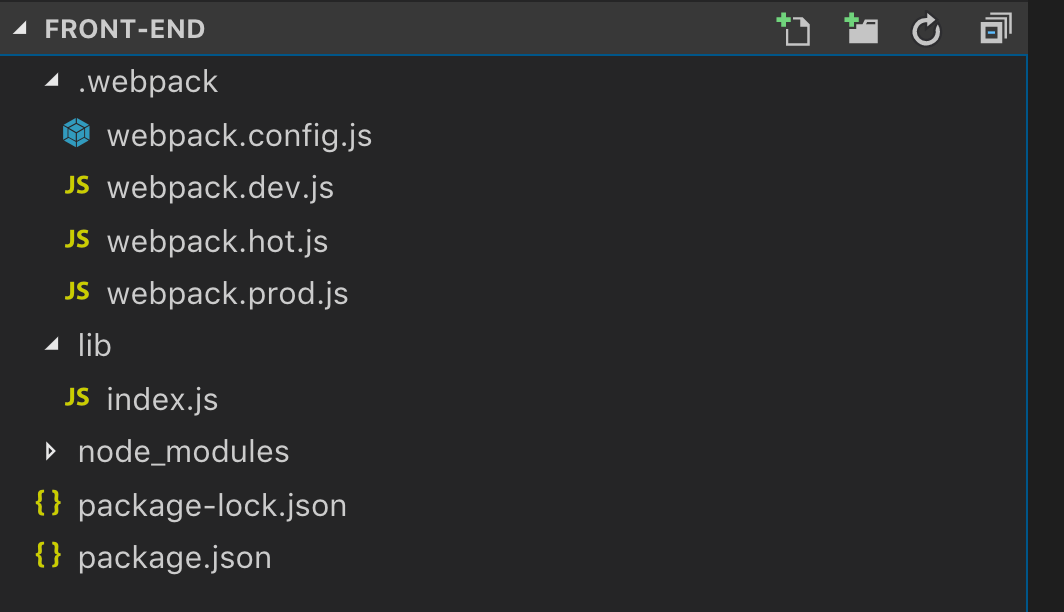

We start by creating a minimum project with React and webpack. For a clean top-tier structure, I like to have all webpack configurations under one folder.

For different environments, a fairly standardized convention is to suffix your files with the environment and use those configurations for the given npm command, such as npm run prod . This gives developers headspace so that they do not need to navigate through the entire webpack configuration to know which part is configured for a given environment.

At this point, the most important part is how you are going to structure the React application. I prefer a top-level folder named lib although src works just as fine.

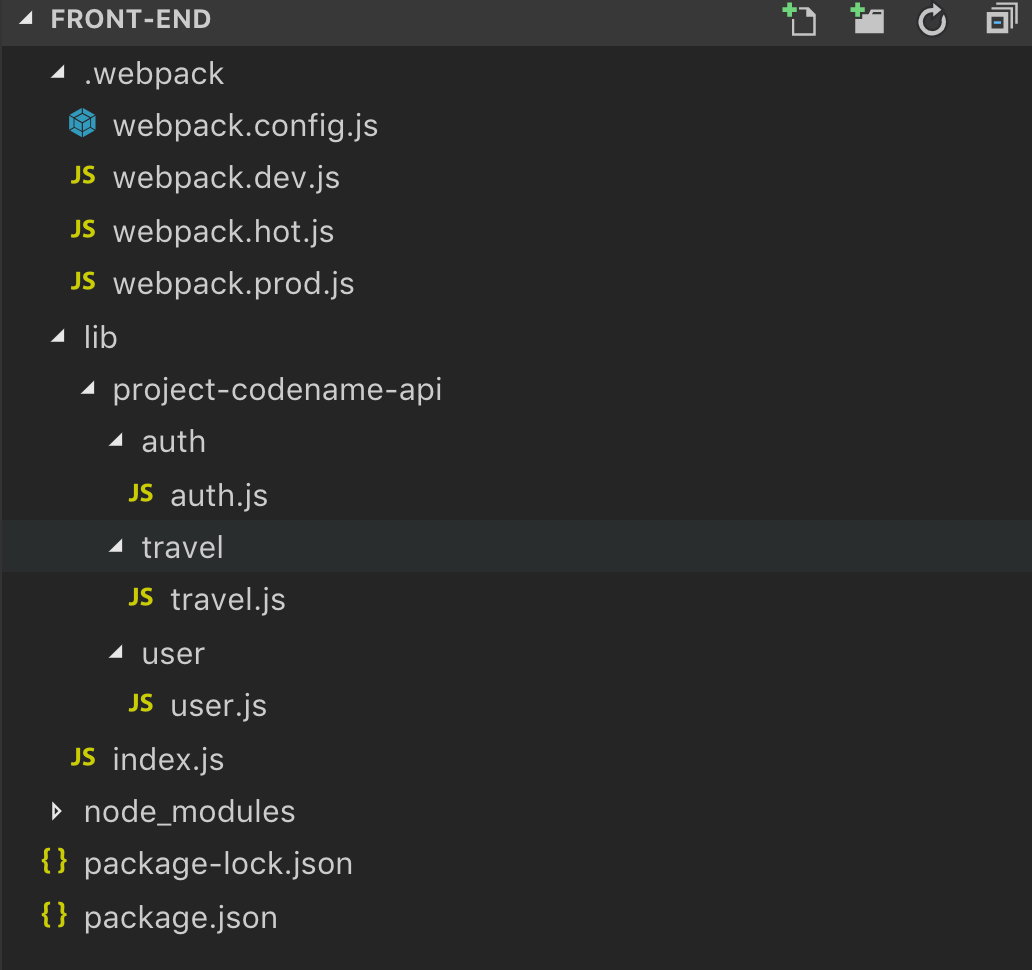

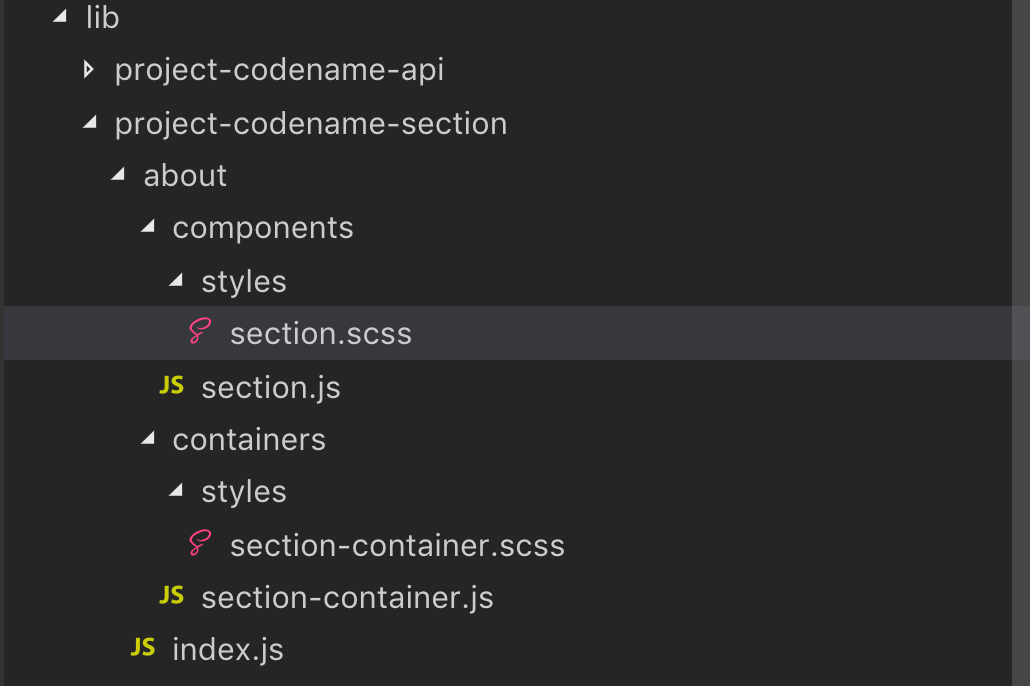

Inside lib is where the important sections are. To make a project readable and maintainable, it is important to make clear separations of concerns. For instance, if you have a REST-API, it is smart to put the Http calls inside their own respective folders.

This setup makes your view (React) cleaner to work with instead of embedding REST-API code in your view folders.

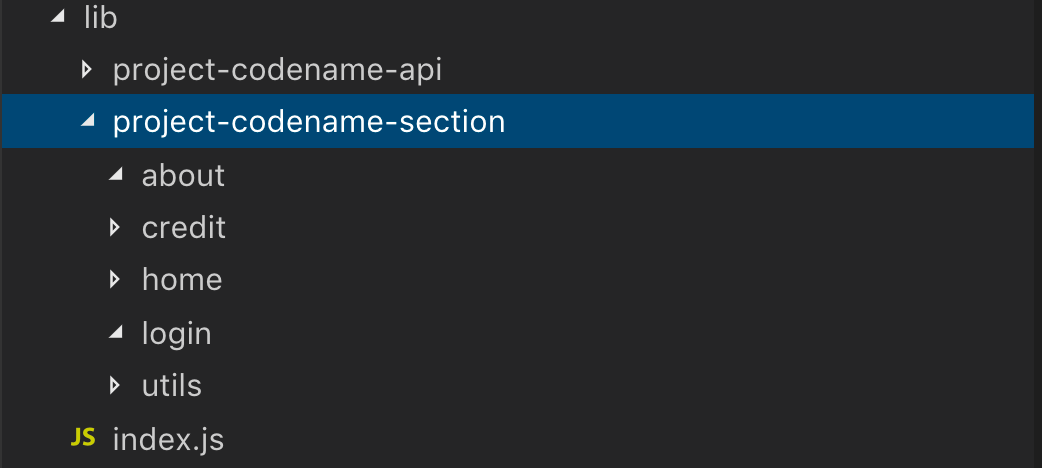

Next up is React. Depending on which phase your project is in, a technique that has worked well in many of projects I’ve been involved in, is to split logic based on different types of services your application offers, or to split based on the types of users your application has. This is up to you, if the users have the same layout, it might be better to split logic based on services you provide.

In this example, your project could have a codename, as well as you might have different stacks on different parts of your application. As seen in the picture above, we split the architecture based on the services that a given application might have.

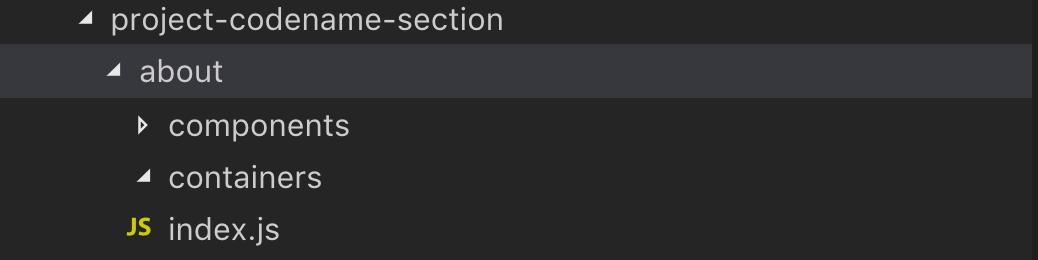

In each of these service folders, we have a 2 folder — 1 file layout. Containers are responsible for fetching and handling data, sending them down to components. This way, a divide between visualizing data and handling data is provided.

For styling, I like to have styles locally for each component so that each component is isolated and it is easy to navigate and edit design without having to use time on global stylesheets. Another variant, is to have a flat style structure, but it will not scale well once there are a lot of components.

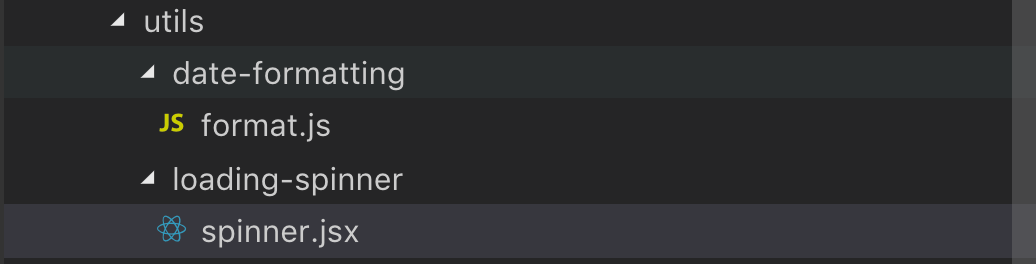

In the utils folder, normally one just has the pure JavaScript functions/helpers that are needed across the application. This might seem smart, but in reality when developing a product there are a lot of situations where your project is a bit noisy, and a good middleway to strike then, is to put your common react components in this folder and abstract it to a private npm package or styleguide later. You can also remove it and move it closer to the folders using it the most (incommon/utils folders) later.

Why is a strict folder structure really needed?

Once you are in the wind and your application has gone through some development, it is more normal to produce code on top of your existing stack instead of having to refactor code to incrementally improve your application.

When the Egyptians built pyramids they didn’t remove two bricks to move the structure, they used blocks to stack up the structure. In this case, you do not usually move big files and re-arrange them every time you do a Pull Request. In that case your team members would think you’re insane doing so.

Instead, developers tend to:

A) Live with a well defined architecture and build layers on top of a solid foundation

B) Develop a unmaintainable until they get depressed and quit, followed up by another developer hopefully starting to refactor the code

The ideal case would be A. Since the market is heavily based on shipping code and making things work, it is obvious that you will need to start with a fresh slate and then build your way up to complexity. In the end, you will save more money as a business, doing the work properly and then focusing on being fast, then rushing to market with an unbearable codebase.

And there are more aspects to this argument, which will often be proved empirically. As a newly hired developer you might get thrown straight into the frying pan without any knowledge of a battlefield of pitfalls. These pitfalls usually are centered around “getting started”, “getting up and running” and so on.

I disagree on that part. Why? It’s a developers job to make the source code easy to navigate around, easy to start and a developer should never be concerned with not being able to do his/hers job because the infrastructure is too much of a headache to get by with.

The contradiction to a well defined structure is clear as opposed to the winning arguments, which is, loosing talent and building a strong engineering team. From a managers perspective, it might be hard to see the profit in investing time making your code look neat opposed to making money, but making money is an in-direct effect of how a developer can use time focusing on development. In this case, maintainability.

Too many bugs in your bed? Replace it, don’t fix it

I’ve been working in the industry for a couple of years now and also with the tooling that drives the industry, and I’ve seen some tendencies towards a bug being a singular case where one thing goes wrong cause the issue is obviously isolated and only occurs this one time and nowhere else. From an analyst perspective, you know that these incidents aren’t really unique but they share a common trait. Once you see more bugs of the same start grouping, the finite solution is to fix the way the system works, not monkey patching an issue since the stack is being replaced somewhere soon anyway.

You, as a developer will save yourself tons of hours debugging, working around quirks and delaying timelines because of this. The problem isn’t the isolated instance, but the un-encapsulated structure of it.

This case is also related to performance , believe it or not. It is unfortunate that we do not have metrics on well-defined structures in applications to those who aren’t, my hypothesis is that we will see the well-defined ones are more performant than those who are smaller in features. Why? It’s a prioritization problem. Larger apps have more work, sure, but they also have the advantage of a well designed architecture.

Conclusion

If you are building an application, do it properly. Define well defaults and make up a good structure for it before starting. It will yield great results in length and even if your traction isn’t big to start with, it will have a longer lifetime than a short-term solution.